Khijou comes back into the living room with her laptop.

“Here he is,” she says.

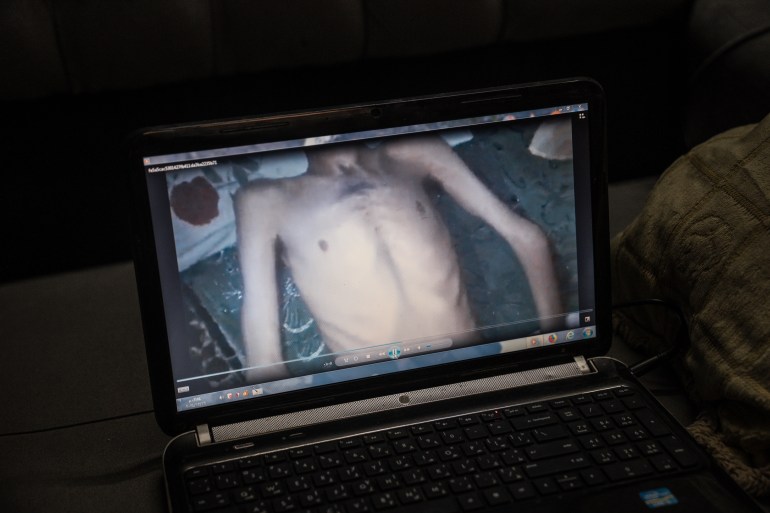

The picture of her son, Samir, is grim. In it, he’s still alive but his limbs are skeletal. He is starving from al-Assad’s siege over Moadhamiyet al-Sham in 2013.

Samir’s ribs jut out from his skin, his bony elbow bent painfully.

Three days later, Syrian officers allegedly kidnapped him after Khijou sent him for medical evacuation with a United Nations convoy. He never came back.

“They took him to the Air Force Intelligence branch, that’s what we were told at the time,” she recalls.

Samir would be 32 years old today, Khijou says – if, by some slim chance, he managed to survive all those years of prison. Other than that, “we don’t know anything”, she says.

Perhaps he went to some other prison, she figures, maybe Sednaya. She is calm and composed at this possibility, a civilian journalist simply pointing out another injustice around her, the years of heartbreak seemingly calcified into the fact of Samir’s likely death.

The chance that he’s still among the survivors becomes slimmer by the day.

Today, Khijou shares his picture and name on social media in the hopes that someone, somewhere, might have information.

Khijou’s other son, Muhammad, who shares a name with his 22-year-old cousin, is also gone. He fled to Germany a year ago through Europe’s forests, the thought of al-Assad’s fall a distant dream.

Khijou supported him in taking the journey, fearing he, too, might get arrested at a regime checkpoint someday and never return.

He’s now stuck in a refugee camp, unable to work or study.

In Khijou’s profile picture on WhatsApp, pictures of the two young men are copy-pasted together side by side, looking so similar – Samir’s clean-shaven portrait from before 2013 next to Muhammad’s more up-to-date beard and moustache, posing in front of a wintry skyline in Germany.

It’s not clear yet what justice might look like for families like the al-Khateebs.

Legal justice for Syrian prison survivors has been limited. In 2022, a German court in Koblenz convicted Anwar Raslan, former head of investigations at the notorious General Intelligence Directorate’s Branch 251 in Damascus, of crimes against humanity. He was sentenced to life in prison.

That case was successful because Germany has implemented “universal jurisdiction”, meaning the country’s legal system can prosecute crimes against humanity and other serious cases no matter where the crimes happened.

“So that is still an option, of course, if any perpetrators are found in a country that implements universal jurisdiction,” explains international criminal lawyer Nadine Kheshen.

Inside Syria, things might be different.

As of now, it’s been less than a month since the fall of the al-Assad regime, so it isn’t yet clear how the justice system could play out for prison victims and their families.

“It’s still not clear how the judicial and legal system will look, at least in the transitional period,” says Obai Kurd Ali, a Syrian lawyer and specialist in international human rights law at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy.

“People are still trying to understand the new system.”

Most important, for survivors like the al-Khateeb sisters and others, is documenting what happened to them in the hopes of future accountability, Kurd Ali says.

The sisters say they are willing to speak to lawyers and hope to someday “file a lawsuit” over what happened to them in prison.

Khijou says she simply isn’t ready to forgive the people who imprisoned her and her family.

“As female detainees, as mothers of detainees, as wives of detainees, we have no forgiveness,” she says, matter-of-factly.

Behind her is the laptop with images of her son Samir’s starved, skeletal body.

His absence still stings.

Khijou’s husband, named Muhammad, now suffers severe depression.

“It’s been two years now that he hasn’t been able to leave the house. He sits with us at home, but quiet. Silent. He doesn’t speak,” Khijou says.

The elder Muhammad is with us, apparently, in the house, as we drink our sweet tea.

But he remains hidden somewhere in the freezing apartment, beyond a series of closed doors, past Mayyasa’s ring light for her makeup videos, and Khijou’s industrial sewing machine.

For now, the family have their quiet anger.

More Stories

Sudan’s military pushes back rebels in second city of Omdurman

NATO, Gaza and Greenland: Key takeaways from Trump’s news conference

Thousands flee as winds drive wildfires into Los Angeles